Medieval Body: Senses

As I write this post an hour before lunch, my hunger makes itself known. The growls of my stomach reach my ears and my hunger is experienced both audibly and physically. I can feel that I am hungry, but others might know, too. (Hopefully no one else can hear my stomach rumbling in adjacent offices). And while hunger is not a traditional "sense," it participates in the body's ecology of sensory experience. As Richard Newhauser writes, "sensory organs were not just passive receptors of information, but actively participated in the formation of knowledge." [1] In many ways, we know what we know - and what we do not know or cannot know - through the senses. Learning how people in the past experienced the world through senses is difficult to do since senses are not universal and certainly are grounded in specific environmental and material conditions of their own time. There has been an uptick in "sensory archaeology" - understanding sensory experience in the past - and medieval texts engage the senses in ways that are both familiar and peculiar.

Human ear complaining to Nature from the Spiegel der Weisheit manuscript (Salzburg, 1430)

This image shows the goddess Nature, clothed in a pink dress, standing against a similarly pink frame. She reaches toward a lush hilltop decorated with flowers and grasses that are also embellished in the blue sky-like background above. On the grassy knoll is an eye and an ear, both somewhat greyscale. The image has been described as the human ear's complaint to Nature, since the eye is fixed not on the goddess but the other body part. The swirling, gold filigree that fills the blue sky-like space almost appears as sound in air - is this what Nature hears? She hears something that the viewer cannot.

I love this image because it purposely dismembers the body to isolate the senses. To a medieval audience, the senses were embedded in three major taxonomies: the external senses, the internal senses, and the spiritual senses. While the external senses are typically capped at five (sight, sound, taste, touch, smell), this was largely inherited from antiquity (think Aristotle's De Anima). Chaucer's Parson, for instance, conservatively keeps the senses in a static formation:

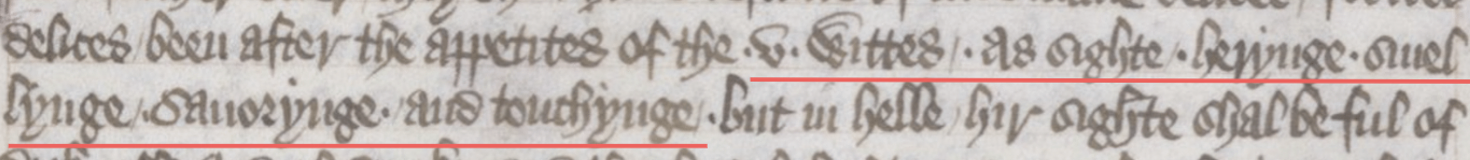

A section from Chaucer's "Parson's Tale" that explains the five senses. Ellesmere MS, f. 209v. Underlining is my addition.

the .v. wittes, as sighte, herynge, smellynge, savourynge, and touchynge

Longthorpe Tower, Peterborough, Cambridgeshire, UK, c. 1320–1340. Text is my addition.

Senses, or "wittes" as the Parson calls them, were understood in a hierarchy - with sight usually taking first place in importance. But the senses were also quite base compared to cognitive processes like memory, perception, and reason. The image below shows a "wheel of senses," riffing a bit on the rota fortunae (wheel of fortune). This is painted in a chamber in Longthorpe Tower (located in Peterborough, Cambridgeshire). The painting is dated c. 1320–1340 and displays a turning wheel with the five senses at the end of each spoke, represented by an animal. The spider's web is touch, the vulture is scent, the ape is taste, the cockerel is sight, and the boar is sound. At the center of the wheel is King Reason, human in form, turning the senses. This image reflects a popular theory of the senses, held by many medieval Christian theologians, that animals were superior to humans in their senses but humans were ultimately superior because they have reason:

Homo in quinque sensibus superatur a multis: aquile et linces clarius cernunt, vultures sagacius odorantur; simia subtilius gustat, aranea citius tangit; liquidius audiunt talpe vel aper silvaticus

In the five senses a human being is surpassed by many animals: eagles and lynxes see more clearly, vultures smell more acutely, an ape has a more exacting sense of taste, a spider feels with more alacrity, moles or the wild boar hear more distinctly

This is from Thomas of Cantimpré's thirteenth-century work On the Nature of Things, a text that tried to explain the workings of the world. The role of "reason" is to control the senses, to guide them to their divine purpose, since the senses were often the entry point to sin.

While the total count of five has stuck, throughout the Middle Ages these five senses split-off, shared, and morphed into various multi-sensory experiences and cognitive processes. Scientific, theological, medical, and poetic discourses had something to contribute to the medieval sensorium, at levels bodily, psychically, and spiritually. In class today, students will be in small groups and given a medieval artifact to engage with. Some will handle a facsimile of a prayerbook, others will take a 360 virtual tour of the Hagia Sophia, others will read fifteenth-century recipes, and others will look at stained glass. It is my hope that students will see the multi-sensory experience of these artifacts and imagine the cognitive and emotional processes that these artifacts conjure.

[1] Richard Newhauser, "The Senses, the Medieval Sensorium, and Sensing (in) the Middle Ages," in The Handbook of Medieval Culture, Vol. 3, ed. Albrecht Classen. (De Gruyter, 2015): 1560.